Though human body parts (heads, hands, &c) were used as charges from the earliest days of heraldry, full human figures did not begin to be used in arms until the 14th Century: e.g., the monk in the canting arms of Mönchen, c.1370 [Gelre 41v]. The usage seems to have begun on the Continent and eventually spread.

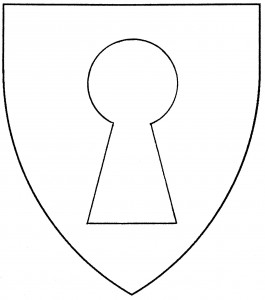

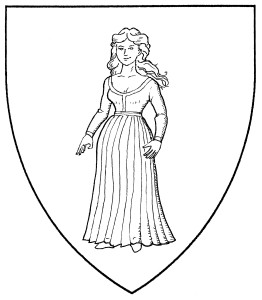

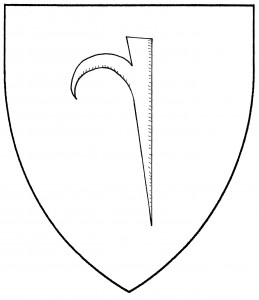

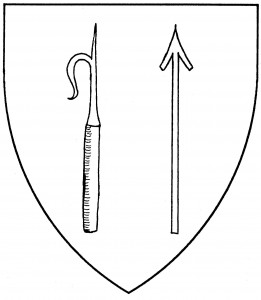

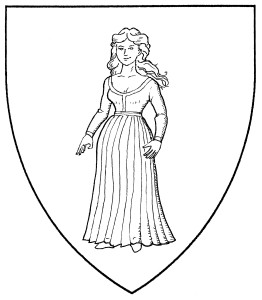

Maiden (Period)

Examples of human types include maidens, children, and old men. Humans seem to be statant affronty by default; when in some other posture (e.g., “passant”), they’re turned to dexter, but even then the torso partially faces the viewer. The exact type of human should be explicitly blazoned.

In period blazon, a human figure “proper” was assumed to be Caucasian (pink or white) unless otherwise specified; Society blazon had once followed this, but is now more inclusive. Human figures proper are now blazoned as one of three categories: “dark-skinned” or “Black” proper, which is sable or a dark shade of black or brown; “brown-skinned” or “Brown” proper, which is any other shade of brown except light tan; and “light-skinned” or “White” proper, which is white, light pink (carnation), or light tan. The first two categories are treated as colors for contrast purposes, and will conflict with one another, all else being equal. The third is treated as a metal, and will conflict with argent, all else being equal. For all three categories, hair tincture should be specified separately.

Human figures are assumed to be vested, but the exact nature of the vesting (especially if in another tincture) may also be blazoned. Lack of vestment should always be blazoned: nudes were not uncommon in period armory, as in the nude damsels (Italian donzelle) in the canting arms of Donine, mid-15th C. [Triv 131], or the nude man in the arms of Dalzell, 1542 [Lindsay].

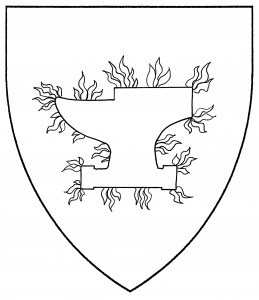

Many human figures are defined by their professions: e.g., the “monk” of Mönchen, noted above; the “builder” (German Bauer) in the arms of Pawr von Stain, mid-16th C. [NW 64]; the “fool” (German Narr) in the arms of Narringer, mid-16th C. [NW 12]; the “miner” in the arms of the Mines Royal Company, 1568 [Gwynn-Jones 105]. Occasionally, a notable figure is blazoned by name: e.g., “the figure of Saint George”. In these cases, the figures are appropriately garbed, without needing explicit blazon.

The “Turk” is mustachioed, and bald save for a long topknot of hair; if he wears a turban, it is explicitly blazoned. When “proper”, he is “light-skinned” with black hair. The Turk is found in the canting arms of Turcha, c.1550 [BSB Cod.Icon 276:123]. Turks’ heads are more often found: they’re frequent in Hungarian armory, a remnant of that conflict during the 16th and 17th Centuries; they are found in the arms of Captain John Smith (of Pocahontas fame), granted 1603 [Volborth 122; Woodcock & Robinson 38-39].

Moor (Period)

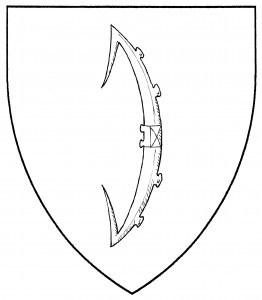

Saracen maintaining a scimitar (Period)

The “Moor” or “blackamoor” is a Negroid human, unbearded and with nappy hair. If he wears headgear (a torse, a kerchief, &c), it is explicitly blazoned. When “proper”, he is “dark-skinned” with black hair. Moors and Mooresses are frequently found, especially for canting purposes, as in the arms of Mordeysen, 1605 [Siebmacher 160].

The “Saracen” is sometimes misblazoned as a “Moor” in mundane armory. The Society has accepted the definition of a Saracen as having Semitic features, bearded by default; his hair, when visible, is long and wavy. He’s most frequently shown turbaned, but some period examples show him crowned or torsed; in any case, the headgear is explicitly blazoned. Saracen’s heads are found, blazoned as “soldan’s (sultan’s) heads” in the canting arms of Sowdan, c.1460 [RH]; the full figure is found in the arms of Thomshirn or Thumbshirn, 1605 [Siebmacher 158]. When “proper”, the Saracen is black-haired, “light-skinned” though a darker tan. (There were rare instances in period of dark brown Saracens [HCE xxxiv]; they should be blazoned “brown-skinned Saracens proper” in Society armory.)

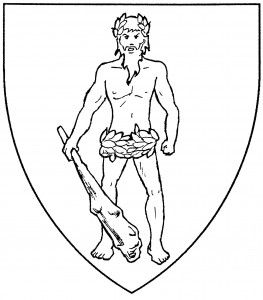

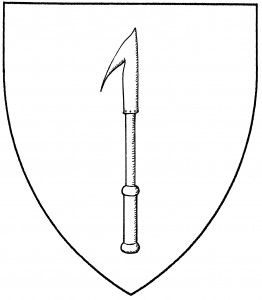

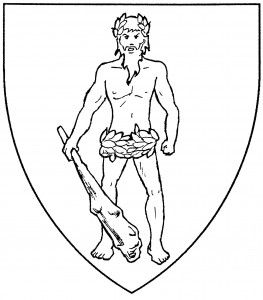

Savage maintaining a club (Period)

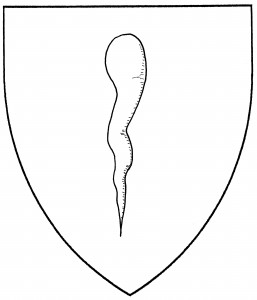

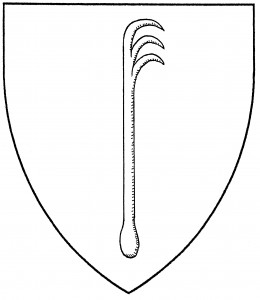

Woodhouse (Period)

There was confusion in period between the “savage” or “sauvage” and the “wild man” or “woodhouse”. Both were wild and unclothed, but the term “woodhouse” referred to a specific form: long-haired, bearded, and body covered entirely in hair (some texts say leaves). This form was found as the canting crest of Sir Thomas Wodehouse, c.1520 [Walden 84; see also Friar 377]. The savage was similarly long-haired and bearded, and sometimes drawn covered with body hair, like the woodhouse; but the better-known form of savage has him smooth-skinned, girded with leaves, and often carrying a club. This form of savage was found in the arms of von Dachröden, 1605 [Siebmacher 149]. The very fact that the woodhouse and savage may be distinguished in English has probably led to their current heraldic definitions; and these are the definitions used in the Society.

Other specific variants include the “Saxon”, unbearded, light-skinned, and blond, garbed appropriately. The “knave” is a boy or youth, defined less by vestment than by attitude: the knave is shown making a rude face, pulling back his lips with the fingers of both hands. He’s found in the arms of Reyßmaul, mid-16th Century [NW 154].

Of blazons peculiar to the human figure, Your Author’s favorite is one taken from Franklyn [215]: a nude maiden, with her arm hiding her bosom, may be termed a “maiden in her modesty”. A human “armed cap-a-pie” is fully armored in plate, from head to foot. A human “genuant” is in profile, kneeling on one knee.

For related charges, see ape, humanoid monsters, mandrake, skeleton. See also glove-puppet.

The Order of the Walker of the Way, of the Outlands, bears: Argent, a palmer, robed, hooded and bearing a staff sable.

Pawel Aleksander od Zerania bears: Azure, a man armed cap-a-pie and maintaining a lance and shield argent, between in chief two plates.

Jimena Montoya bears: Gules, a demi-maiden in her modesty and on a chief embattled argent a sword fesswise gules.

Martha Elcara bears: Azure, a nude blonde baby sejant erect to sinister, legs crossed proper.

Wulfgifu Wadylove of Wokyhole bears: Argent, a savage rampant and on a chief wavy azure two hearts argent.

Sofia Staritskaya bears: Per pale vert and sable, Saint George mounted and passant contourny, spear piercing a dragon in base within a bordure Or.

Sely Deth bears: Per pale gules and sable, a demi-knave vested and capped, pulling back his lips with his fingers argent.